Written by Brendan O’Meara

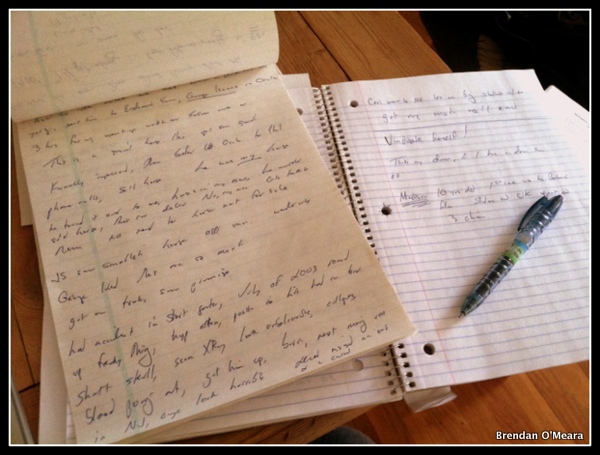

My big writer’s resolution of 2014 was to do more immersion projects. I stopped covering high school games. I’ve covered hundreds upon hundreds of games. They’re not worth my time any more in a very small media market.

The best thing any writer can do is to do interesting things (or do things the writer finds interesting). The technical skills that come with writing comes with repetition.

The literary agent Jeff Kleinman visited Goucher College one summer residency. This was in 2007. He rattled a lot of cages for harping on the MFA program for producing what he loathes: the MFA Voice. The MFA Voice is subjective, of course, but it’s a voice that is technically sounds but almost always devoid of energy, spunk, and edge. It’s a voice that is bogged down by fundamentals, that’s too aware of itself, that doesn’t want to get in the way of the story. It can be very vanilla. Take movies. You know when you’re watching a Wed Anderson, a Christopher Nolan, a Stephen Spielberg, a Quentin Tarantino. That’s voice. We want to occupy their brain space for two to three hours at a time.

Certain stories that are very heavy need the author to step back, but for most stories, especially memoir, the voice has to be engaging and full of energy. The key, as Austin Kleon writes in his great book Show Your Work, is to “Be an Amateur.”

Amateurs are not afraid to make mistakes or look ridiculous in public. They’re in love, so they don’t hesitate to do work that others think of as silly or just plain stupid.

That’s what Jonathan Safran Foer did when he wrote Everything is Illuminated. He wrote like an amateur. In Malcolm Gladwell’s What the Dog Saw, Gladwell wrote a great piece on late bloomers (Foer is not a late bloomer, but the other side of the coin). Foer brought an amateur approach to his writing. He was a freshman at Princeton (smaht kid, as we say in the Boston area). On a whim, he took a creative writing class with Joyce Carol Oates. Gladwell wrote:

Oates told him that he had the most important of writerly qualities, which was energy. He had been writing fifteen pages a week for that class, an entire story for each seminar.

“Why does a dam with a crack in it leak so much?” [Foer] said with a laugh. “There was just something in me, there was like a pressure.”

Foer went to Ukraine to see where his grandfather came from (doing cool stuff). He came back. Foer said:

I was just writing. I didn’t know that I was writing until it was happening. I didn’t go with the intention of writing a book. I wrote three hundred pages in ten weeks. I really wrote. I’d never done it like that.

This is the type of thing that gets a bit smothered in the MFA crowd, a crowd that gets bitter when their technically sound prose can’t find a home. It’s like what Kleinman told me once, “It doesn’t matter how great a writer you are if you’re not writing anything people want to read.”

I’m writing about maple syrup these days. It’s cool. It’s about syrup, but it’s also about my fleeting sense of manhood and a search for brotherhood. Anyway, go ahead and watch some sap dump into the holding tank. I think it’s interesting.

View on Zencastr