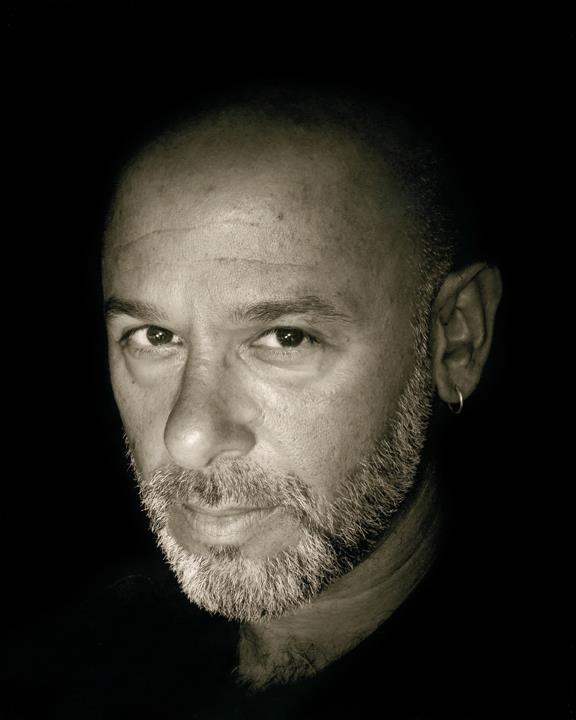

By Brendan O’Meara

Tweetables by Jane Friedman (@JaneFriedman):

“You can’t expect to remain static.”

“You have to decide how you want to live in this ecosystem that is morphing around you.”

“So much of my career, it’s been a process of realizing that the “book” isn’t everything.”

Promotional support is provided by Hippocampus Magazine. Its 2018 Remember in November Contest for Creative Nonfiction is open for submissions until July 15th! This annual contest has a grand prize of $1,000 and publication for all finalists. That’s awesome. Visit hippocampusmagazine.com for details. Hippocampus Magazine: Memorable Creative Nonfiction.

Okay, back in the saddle again, it’s the Creative Nonfiction Podcast, the show where I speak to the best artists about telling true stories so you can apply those tools of mastery to your own work.

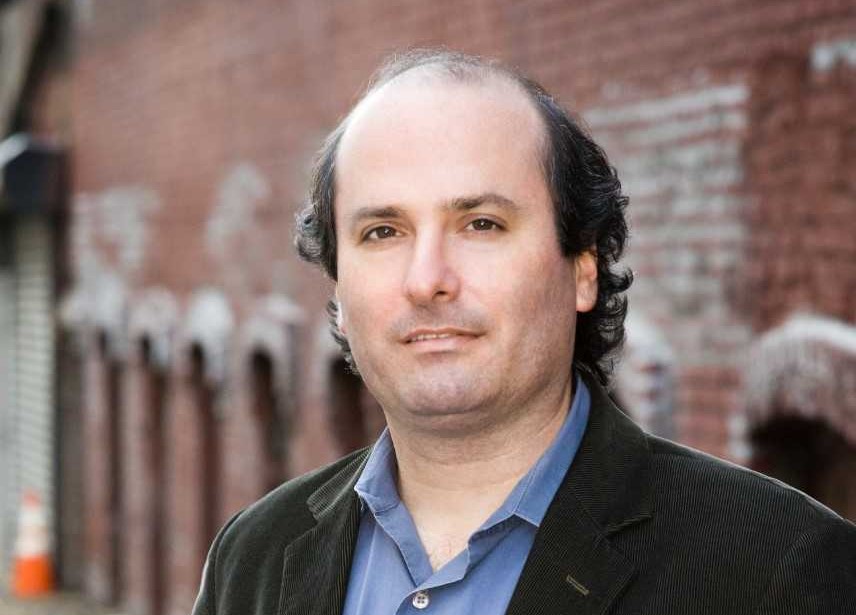

For Episode 102 of CNF Pod, I welcome Jane Friedman, the titan (though not like Thanos) of the publishing industry, whose book The Business of Being a Writer, published by the University of Chicago Press, is the best and most frank book on earning a living with words.

It debunks a lot of myths and, quite honestly, could save a bunch of people from getting into the biz on false delusions and might even save more people from pursuing an MFA (not that this is/was Jane’s intent), a degree, IMO, that leads to more debt than fulfillment, controversial as that may be. And I have one, earned on the false pretenses of career advancement, but that’s not why we’re here.

Jane talks about her upbringing in a small Indiana town, I wish it was Pawnee, but it wasn’t.

- How a writing career is very much individualistic

- Dealing with shame

- Playing the long game

- Embracing Change instead of fighting it

- And getting beyond the idea that the book is the be all, end all

Thanks to Jane and to our promotional sponsor Hippocampus Magazine.

If you have a minute or two, please consider leaving a review on iTunes/Apple Podcasts. That would mean the world to me and will help this podcast reach more people looking to tell their best true story.