Written by Brendan O’Meara

I listen to Brian Koppelman’s podcast, The Moment, every week. I’ve read a bunch of books written by Seth Godin. So when Koppelman interviewed Godin on The Moment my iguana brain almost hemorrhaged.

Koppelman brought up Godin’s The Dip: A Little Book That Teaches You When to Quit (and When to Stick). It was a formative book for Koppelman. I bought it on my Kindle. I read it in an hour on a Tuesday. Then I read it again on Wednesday. In my extensive morning journaling, I wrote for a few days on the Dip as it applies to freelance writing.

Let’s first define the Dip as Godin writes early on:

If you learn about the systems that have been put in place that encourage quitting, you’ll be more likely to beat them. And once you understand the common sinkhole that trips up so many people (I call it the Dip), you’ll be one step closer to getting through it.

Extraordinary benefits accrue to the tiny minority of people who are able to push just a tiny bit longer than most.

Godin also writes, “The Dip is the set of artificial screens set up to keep people like you out.”

It’s only natural to read these things through your own subjectivity. It got me thinking what the “artificial screens” to being a freelance writer and author. Here’s what I know from living in the Dip.

- Low pay/No pay

- Low pay that doesn’t arrive on time

- Low pay that doesn’t arrive at all

- Having to chase down payment

- Rejection

- Loneliness

- Lack of validation/appreciation

- Killed stories

- Constantly having to hustle

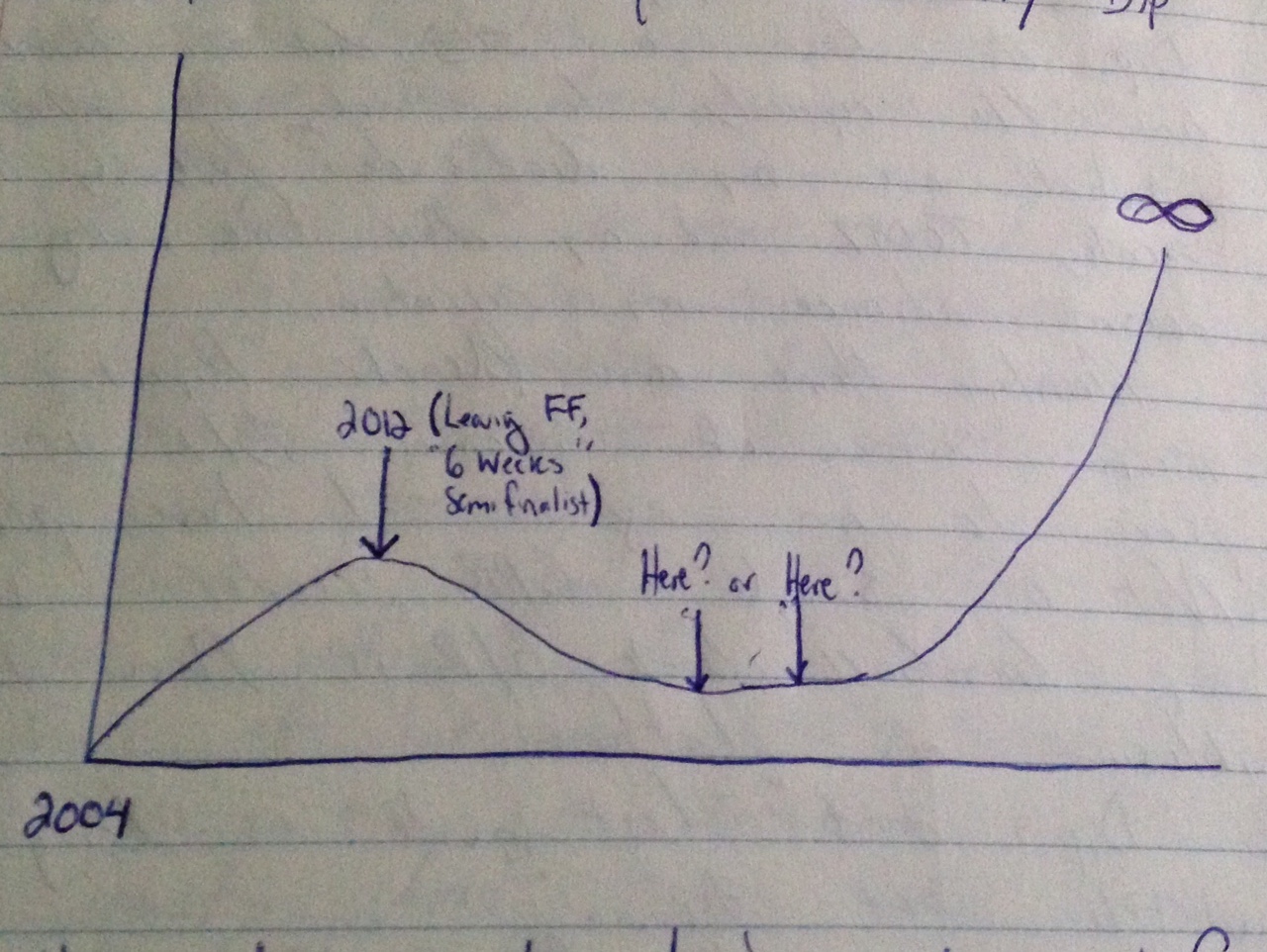

There’s probably more, but you get the gist. Another point to consider—and what Godin makes you ask—is: Am I in a dead end or am I in a Dip? Here’s my Dip:

If it’s a dead end, you need to quit yesterday. I’d say most reporter jobs at newspapers are dead ends. You have to leave the newspaper to get a promotion or you need to be a hard core freelancer like my friend Brian Mockenhaupt. At least in that instance you can pick your spots. That’s how the great Michael Paterniti did his work.

In order to recognize if you’re in a Dip or not, you need some form of validation. You need to have talent. Work ethic is a given, but you need to have some talent and that talent needs validation while in the Dip. That validation gives you the strength to remain in the Dip and lean into it, to push through it to the relative bounty on the other side.

I’ve known countless writers and colleagues who gave up. The Dip killed them. The Dip filtered them out and now there’s less in the Dip for you and for me.

While in the Dip you need to publish something of merit at a higher profile magazine or literary journal. Or, if you pitch a high profile magazine (and get rejected) and the editor is nice enough to reply, he/she needs to say a positive thing or two about your pitch. When you get these micro victories, you know it’s a matter of time.

Blogging doesn’t count. Self-publishing doesn’t count. The former is good practice for connecting and for getting words down; the latter is a shortcut (however, if you somehow prove to sell tens of thousands of copies, then you can tell me to shove it. And God bless you!). There must be an external validation to justify remaining in the Dip. It’s ugly in the Dip. It’s dark down here. I mean, it’s dark. It’s grim. At least my Dip is grim. My Dip is the freakin’ Hunger Games. If yours is better, can we get coffee?

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve thought of quitting. In the last two weeks our Civic needed $691 worth of repairs. Our Accord needed $600. Our dogs needed semi-annual checkups for $430. I’ve thought about quitting today. I’m thinking about it right now.

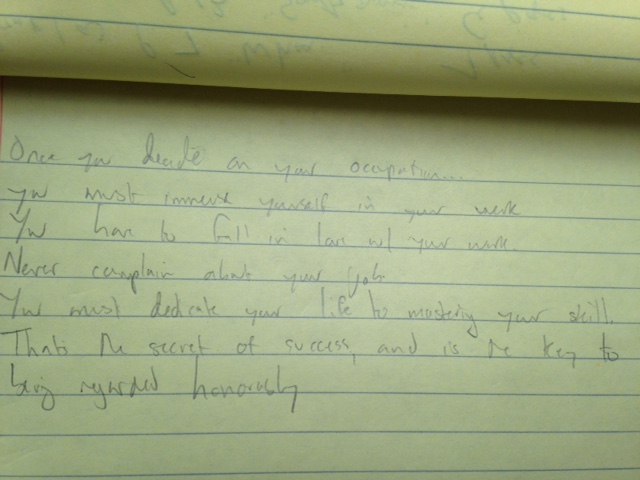

The people on the other side of the Dip? Talk to them they tell you the same thing: Write every story like it’s for a Pulitzer and query like hell. Turn work in ahead of time. Make editors’ jobs easier so they come to you in the future.

I’d add another thing: Have fun. Have fun while writing. We could be shoveling coal or pumping septic tanks. When you have fun with this crazy craft, it shows on the page. Don’t be self loathing (I’ve been guilty of that. That’s bad, bad practice.). Don’t complain. Have fun. The more fun you have, the better equipped you’ll be to get through the Dip.

A great sister book to The Dip is The War of Art. I’ll write about that another time.